ABUSE AND COMMUNITIES

No matter what our upbringing is, we all have ingrained beliefs about abuse, church structure, authority, and victimization. Maybe you’ve seen this book lying on a friend’s bookshelf or advertised on social media and you’ve already decided your response without reading it. Dylo Cadet’s story of abuse from an Anabapist missionary to Haiti is upsetting and divisive, yet it needs to be heard. We cannot ignore hard stories and questions just because they are uncomfortable. Our human tendency is to defend what and whom we know, but sometimes that comes at the cost of justice and truth. As Dr. Diane Langberg says: “We must not assume that our family, church, community, country, or organization is always right just because the people in it use the right words.” Read Dylo’s story and listen to what he says, then wrestle with what his questions mean in your context.

My goal for this review is to give a summary of what Cadet shares in his story while asking questions about our own communities and organizations.1

“INTRODUCTION” 2

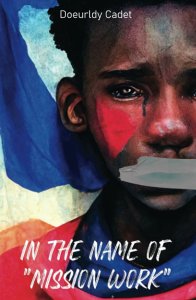

Doeurdly “Dylo” Cadet published In the Name of “Mission Work” in December 2022, explaining his abuse from Jeriah Mast. In 2019, Mast, a former Christian Aid Ministries (CAM) worker in Haiti, “admitted to law enforcement that he molested 30 or 31 boys in Haiti over a span of about 15 years,” as well as two boys in Holmes County, OH, where Mast was from.3 He was found guilty of the abuse of the two Ohio boys and is currently serving a nine-year sentence.4 CAM’s response to this situation in 2019 declared that the CAM Board of Directors “was not aware of any sexual conduct between Jeriah and minors until 2019,” but that two of their managers had known about accusations against Jeriah Mast since 2013.5 CAM then placed those two managers, Paul Weaver and Eli Weaver, on administrative leave. Dylo’s book presents his perspective on this situation.

Born and raised in Haiti, Cadet grew up in a conservative Christian family. His parents pastored different churches, and Dylo recalls Sunday Bible studies that “established the authority of the Bible in the church from the beginning” (16).6

The first few chapters of the book explain this church setting, outlining the leader’s responses to families (36–37, 49), rules that “were enforced as if it were a military base” (26), and partiality in the congregation (27). Cadet shares this, to “explain how much I have always struggled to reconcile the teachings I heard with the actions of the teachers” (40), a repeated question throughout the book. What should people do when the teachings of leaders directly contradict their actions?

“SHATTERED HOPES”

When Dylo was a teenager, his church connected with Anabaptists (a group from Charity Missions in Ephrata) during some revival meetings. This was his first introduction to Anabaptists and would also be when Jeriah Mast abused him (61–62). It might be important to note that Jeriah was not at this time working under CAM, although he had already spent some time in Haiti and “knew some Creole” (59). Cadet explains how Jeriah Mast then abused him during those revival meetings and how his Haitian leaders reacted when Dylo finally worked up the courage to tell them what had happened. “After summoning all my courage to reveal my embarrassment and confusion, I was devastated when the people [the Haitian leaders] I reported it to refused to believe me” (62). That this happened is tragic, and we should mourn the response of these leaders.

Seven years later, in 2013, Dylo was told that his brother and a friend had also experienced sexual abuse at the hands of Jeriah, who was then working for CAM (75). The three men contacted another CAM worker, Steve Simmons, who heard their accounts and compiled them into a report (76). According to Cadet, that report (parts of which are given in the book), was given to CAM. Dylo says, “Although I don’t know who all saw it, I am confident that some of the leaders learned about the crimes it detailed” (85). Referring to CAM’s response in 2019, only two men knew about this report. After this report, Jeriah was sent back to the US, later married, and then returned to Haiti “with a shocking lack of accountability” (85). Besides this, nothing else was done by CAM after receiving this detailed report. Regardless of the organization, this should never happen. Churches and schools and ministries should use this as a lesson to ask, “What is in place here to prevent anything like this from happening? Who is responsible for keeping leaders accountable? Do we believe stories of abuse, or do we dismiss them as ‘fiction’ or ‘exaggeration’ and continue with normal life?”

“WORKING WITH CAM”

In 2014, Cadet began working for CAM as an interpreter, often seeing Jeriah Mast around the compound (93). He explains why he decided to work for CAM even while his abuser worked on the same compound. In 2019, a group of men from Petit Goave, another community, sued Mast, bringing to light the events from previous years (94). Dylo recounts, “My heart sank as it dawned on me that we three from the report were not the only victims and that CAM obviously had not taken care of the issue after receiving the report” (95). Dylo and his brother sent a letter to CAM explaining how they were reacting to this news and “described being forced to relive as adults what had happened to us years ago” (96). When people discovered that Dylo had been one of the victims years ago and yet had later decided to work for CAM, they questioned the change of tone, considering that he had been a CAM employee for years and currently was. A few contacted Dylo and “tried to make me feel like an ungrateful traitor” (96). Dylo explains that he “never wanted to be known as one of Jeriah’s victims nor did I intend to go public with my experiences” (97).

“FALLOUT”

One of the hardest chapters to read in In the Name of “Mission Work” describes Dylo’s perspective after Mast’s actions became public in 2019. Titled “Fallout,” this chapter explains what Cadet heard from the other victims. He describes how a victim remained quiet because Jeriah promised to “buy him a vehicle” (99). He was told how Mast would go to a “particular orphanage” enough times that “the boys who saw his arrival knew from experience that it was going to be a horrible night…. Some of the boys used pieces of rope to tie their little shorts so tightly they ended up cutting themselves” (101). Worse of all, Dylo describes how Jeriah would reassure the victim “while committing the crime… and then loudly pray to God for forgiveness afterwards” (99). All followers of Jesus should weep and be incensed at this hypocrisy.

“SHIFTING BLAME”

Cadet explains how CAM scrambled to respond to the lawsuits and publicity that quickly came. In talking to an unnamed committee member, Dylo asked “What if, in order to make this right, the mission had to pay X amount of money,” using a purposely exaggerated number (126). The member replied, “If I exploited the situation and made the mission pay too much to settle, that would be like stealing food off the plates of the poor people that CAM is supporting” (127). This interaction raises questions that should be asked about any organization in a situation like this: who are we supporting here—the victims or the reputation of the organization? Are we deeming the feeding of “poor people” more (or less) valuable than finding justice for victims?

In a later interaction with CAM, Dylo was told that CAM might pay up to $20,000 for restitutions, “but the victim would have to sign a paper promising not to pursue any legal action against the organization” and sign “a nondisclosure agreement (NDA) agreeing not to disclose the abuse or the terms of the settlement” (131). Dylo responded to this by asking valid questions: “What would signing an agreement imply? What if it took more than $20,000 for some victims to get a fresh start? What if a victim wanted to share his experience as a testimony to help others?” (131) Other questions could be asked: If this was your child, what price would you put on his or her virginity, on their innocence? Would you agree to sign an NDA?

“FOUNDATIONS OF FAILURE”

Cadet goes on in his book to explain different questions about CAM that he was having even before the publicity of the sex abuse scandal in 2019. He observed the “flawed belief that Haitians are used to misery and therefore should be satisfied with any kind of treatment” (137). At the pastoral training events that CAM hosted (and Dylo translated at), both American and Haitian pastors lived at the compound and spent time preparing their lessons. The two Haitian pastors had to share a less-private bedroom while empty, air-conditioned apartments sat across the compound. When Dylo questioned this (after being told that those private rooms were for guest teachers), he was told by the program manager (who had inquired up the chain of command) that “the apartments [were] reserved for foreigners only” (140).

Dylo discusses this prejudice, asking questions about mission organizations that make statements like this. He says, “When missionaries openly declare that they’re concerned about treating Haitians too well and spoiling them, a predator may feel that he’s treating his victims as they deserve” (149). Dylo also shares the questions he had surrounding the report that had been submitted years earlier: “What was done about the report we sent to CAM in 2013…? How many people from the organization really knew?” (155).

“COMMITTED TO MEDIOCRITY”

One of the most important chapters in this book raises questions that every organization needs to address. Dylo lists mistakes that were made (which will inevitably happen regardless of the place or organization) but wonders if “CAM’s preferred approach was trial and error instead of prevention and education. The very complexity of the work becomes an excuse whenever there is an issue” (160).7 Seeing this lack of training, Dylo draws an analogy to the eye surgeons he went to for various surgeries and the pilots who flew his planes. He “trusted the institutions and processes by which they were trained, certified, hired, and supervised… But when it comes to positions that can impact people’s souls and destiny, we tend to gamble with them and figure it out as we go” (161).

This is a truth that may not be ignored in churches, mission entities, or schools. Training should be given, because as Dylo wonders, “Shouldn’t our institutions be even more careful than hospitals, airlines, mines, or data centers?” (161). He acknowledges the good work ethic that he saw in leaders and missionaries but emphasizes that “in certain situations, a good work ethic is not enough” (163). Too often, mission organizations or schools take “any warm body” that’s willing to go and throw them into situations involving complex relationships, cross-cultural misunderstanding, and the souls of people with little to no training. This is an opportunity for lament—when will we learn to stop repeating the same mistakes that we’ve been making for years across communities?

Often, when scandals rock organizations, people dismiss the victims, saying “But look at how much good the organization has done.” Maybe instead, we should be saying, “At what cost is this good coming? How much harm is being done? Who decides the scales of how much good outweighs the bad? Is it ever justified to point to the good being done to excuse abuse?”

“THE NEXT STEPS”

One of the final chapters, “The Next Steps,” offers ways to respond to abuse situations. Dylo affirms that “a big enemy in this fight is ignorance” and pleads for openness, education, and honesty around the topic of sexuality within the church (187). When the church is silent about sexuality, especially to children and youth, the only voice being heard is from the world, the voice that Satan uses to deceive and entrap.

Satan is doing everything that he can do to twist and distort sexuality, something God created as good and beautiful. What is the church doing to address this attack? Sexuality, a metaphor for God’s desire for intimacy for us through His Son and the Holy Spirit, directly affects our spiritual lives. We should mourn when we read Dylo’s story—this is not the way things ought to be. However, our grief must turn into action.

SUCCESS AND FAILURE

In the Name of “Mission Work” is only one of many stories of sexual abuse within Anabaptist organizations, and it should compel us to take a step back and evaluate the communities and organizations we are a part of. We must remember, as Diane Langberg says, “People are sacred, created in the image of God. Systems are not.”8 Often, we measure success by an organization’s yearly budget, volunteer numbers, or church members. Maybe we’re ignoring other signs of what success and failure are.

We fail when we ignore, silence, or resist victims for the sake of the “organization.”

We succeed when we equip people with the ability to communicate cross-culturally, with education and a Biblical perspective about sexuality, and with consistent and continual evaluations.

We fail when stories like Dylo’s and the thirty other victims are ignored for years.

We succeed when we sit with victims, weep with them, and allow them to come to forgiveness on their time.

We fail when we try to “fix” crimes by keeping issues hidden within churches and not following the laws of our nations to report felonies.

We succeed when we hold people, no matter their ranking, experience, or membership, to the legal, spiritual, and relational consequences of their actions.

Please hear Dylo Cadet’s story. Use it as a catalyst to propel you to lament, outrage, then action—this need not be the norm in the Church. And finally, keep hope that when the Holy Spirit works through followers of Jesus, redemption does come.

References:

1. Langberg, Diane. Redeeming Power: Understanding Authority and Abuse in the Church. Brazos Press, 2020.

2. Roo ney, Jack. “Jeriah Mast sentenced to nine years in prison for sexual abuse.” The Daily Record, November 5, 2019. https://www.the-daily-record.com/story/news/crime/2019/11/05/jeriah-mast-sentenced-to-nine/2365586007/, Web accessed May 18, 2023.

3. “Former CAM worker sentenced to 9 years.” Anabaptist World, November 11, 2019. https://anabaptistworld.org/former-cam-worker-sentenced-to-9-years/, Web accessed May 18, 2023.

4. “An Open Letter from the Board of Directors of Christian Aid Ministries Regarding the Case of Jeriah Mast.” Christian Aid Ministries, June 17, 2019. https://christianaidministries.org/haiti-abuse-case/public-statement-haiti-investigation/, Web accessed May 18, 2023.

5. Cadet, Doeurdly. In the Name of “Mission Work.” Father and Child Inc., 2022.

Footnotes

- While online sources of this cannot be found, it might be something for the reader to know that Dylo Cadet sued CAM because of what Jeriah Mast did to him. While I do not have written proof for this next claim, I did hear that Dylo lost his case because Jeriah Mast was not a CAM employee when he abused Dylo (as mentioned in my article). For some, this fact turns Dylo’s story into a “rant” against CAM. I believe that we still need to listen to what Dylo has to say (especially about his time working for CAM) and then ask questions about our own organizations.

- All headings in quotation marks are chapter titles from In the Name of “Mission Work.”

- Rooney, Jack. “Jeriah Mast sentenced to nine years in prison for sexual abuse.” The Daily Record, November 5, 2019. https://www.the-daily-record.com/story/news/crime/2019/11/05/jeriah-mast-sentenced-to-nine/2365586007/, Web accessed May 18, 2023.

- “Former CAM worker sentenced to 9 years.” Anabaptist World, November 11, 2019. https://anabaptistworld.org/former-cam-worker-sentenced-to-9-years/, Web accessed May 18, 2023.

- “An Open Letter from the Board of Directors of Christian Aid Ministries Regarding the Case of Jeriah Mast.” Christian Aid Ministries, June 17, 2019. https://christianaidministries.org/haiti-abuse-case/public-statement-haiti-investigation/, Web accessed May 18, 2023

- All quotes with page numbers in parentheses are taken from In the Name of “Mission Work.” Cadet, Doeurdly. In the Name of “Mission Work.” Father and Child Inc., 2022.

- “Thank you to the many believers who are praying and waiting patiently for our team to find its way. This case has strained our human ability to process and comprehend why anyone would harm children and abuse trust.” This statement from CAM comes from “An Open Letter from the Board of Directors of Christian Aid Ministries Regarding the Case of Jeriah Mast.” Christian Aid Ministries, June 17, 2019. https://christianaidministries.org/haiti-abuse-case/public-statement-haiti-investigation/, Web accessed May 18, 2023

- Langberg, Diane. Redeeming Power: Understanding Authority and Abuse in the Church. Brazos Press, 2020.